A White House on Paradise Street

This project is inspired by the absence of what has been claimed by some writers to be the first photographic image made in Birmingham and potentially the first image made in England using the daguerreotype process*1. The image is said to have depicted a White House on Paradise Street and is thought to have been made by George Shaw in late August or early September 1839.

This new artwork by Jo Gane in collaboration with photographic historian Pete James and digital artist Leon Trimble combines historic and contemporary techniques to extend the latent possibilities of this missing image.

In response to research by Pete James, the exhibition places small time-machine camera devices around the city in locations relevant to key moments and events in the early history of photography in Birmingham. These devices are constructed using historic techniques in mahogany by master cabinetmaker Jamie Hubbard, to resemble the Wolcott daguerreotype camera patented in 1840. Leon Trimble has hacked the cameras with Raspberry Pi’s, making them able to live stream analogue images from inside the camera back into the gallery space and online. As time machines, these devices mine the contemporary landscape to make visible the history of the city’s role as the ‘midwife to the birth of photography’*2 in the early 19th Century.

Alongside the live streams of indistinct, soft images from within the camera devices, which are reminiscent of even earlier attempts to produce photographic images a series of sharp, detailed new Daguerreotypes by Jo Gane produced at Mike Robinson’s Century Darkroom render fragments of what may have been visible on Shaw’s original Daguerreotype plate into focus within this new digital landscape, inspired by fragments of the past.

*1 Daguerreotypes are one of the first methods of making a photograph invented in August 1839 by Louis Daguerre in Paris, using a highly polished sheet of silver plated copper which is made light sensitive by fuming over iodine then developed with hot mercury before gilding with a gold chloride solution to produce one-off images that appear as if they are a ‘mirror with a memory’.

*2 from Birmingham Reminisces (Second Series) ‘The Pioneers of Photography in Birmingham,’ Birmingham Daily Mail, 28th January 1880

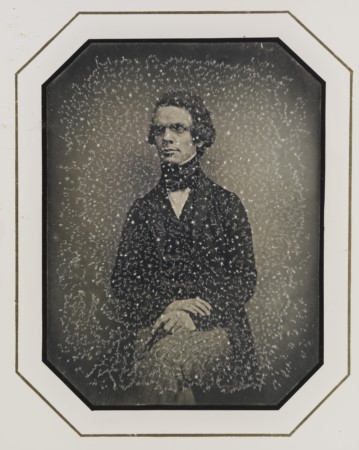

George Shaw (1817-1904)

In his obituary George Shaw is described as one of Birmingham’s ‘most remarkable although not specially prominent characters.’ The son of a Black Country glass seller, he suffered ill-health in his youth and was unable to attend school. His self-education was so successful that in 1837, at the age of twenty, he was appointed Professor of Chemistry at the Birmingham Royal School of Medicine. The School moved to Paradise Street and became Queen’s College in 1843 by Royal Charter. Shaw was afterwards appointed as a teacher of Chemistry and Physics at King Edward’s School, New Street in the early 1850s.

As a Patent Agent, Shaw joined the practice of Luke Hebert in Birmingham in the late 1830s, purchasing the firm from Hebert around 1845 and operating from offices in Temple Street throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. In this role he acquired a uniquely detailed knowledge of the manufacturers of Birmingham and became a key figure in the organisation of the Arts and Industrial Exhibitions held in Birmingham during the mid-nineteenth century. He was subsequently appointed a juror at the Great Exhibitions of 1851 and 1862. He published the first manual on Electro-Metallurgy in 1842, revised in 1844.

Shaw was widely known to the scientists of his day. He lectured on scientific subjects at the Old Mechanics’ Institute, Newhall Street, to the members of the Birmingham Philosophical Institute in Cannon Street and at the Royal Institution in London. After meeting Shaw, Michael Faraday is said to have remarked “In many things I am to him a child.”

With a taste for the arts, Shaw amassed a collection of engravings by J. W. M. Turner, was a capable watercolorist and served as Correspondence Secretary at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists in the 1870s.

Shaw was undoubtedly a pivotal figure in a small group of pioneers who introduced Photography to Birmingham in 1839. There are a number of unconfirmed reports that he produced a daguerreotype of a White House in Paradise Street, within two days of the publication of working details of Daguerre’s process in August 1839. One of these suggests this was the first photograph taken in Birmingham, adding that “there is every reason to suppose that this was the first daguerreotype taken in England since Mr Shaw’s position as a patent agent would enable him to obtain the specifications without delay.” The image remains unknown.

About the Cameras

The camera devices in this project are time-machines, offering a way in to reflection upon the past within the contemporary cityscape.

The camera design used for this project is based on the Wolcott daguerreotype camera which was patented in 1840. The camera uses a mirror rather than a lens to focus the image, allowing for much more light to enter the camera and shortening exposure times, making daguerreotypes much easier to produce and allowing for the production of better quality portrait images.

The Wolcott camera is incredibly rare, with only two known surviving original examples in the world, one of which is held in the collection of Birmingham Museum. This original device has been 3D scanned for the exhibition and a visualisation of the object is available to view in the gallery at BOM.

This camera design has been used due to its technical innovation. The image is projected inside the camera onto a central screen and appears to float within the body of the camera, in a way which is particularly ephemeral, lending itself to our filming of this projection using miniature Rasberry Pi cameras placed within the camera bodies.

To view a video from one of the cameras plase follow the links below.

Performance

Ex-Live Stream from Paradise Street